Discover rewarding casino experiences.

|

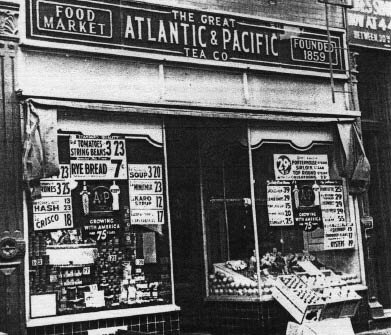

The two George’s had neither achieved the success they’d hoped for. In fact, Hartford only twenty-six, had had a “steady lack of success in dry goods.” Why not now, they asked themselves, buy a ship load of tea and distribute it themselves thus eliminating all the middlemen. Each of those steps would cut down on costs and they could sell the tea for 30¢ a pound. After testing the idea and foreseeing no big problems, they opened their storefront that eventually occupied 31, 33, 35, 37 on Vesey Street. They painted it a blazing red with gold trim, a color combination that became their trademark in the years to come. A huge letter “T” was hung on the exterior announcing their product. Gas lights lit the store, one of the first illuminated commercial businesses to use them. Red and gold bins inside held the “romantically” named teas ... Spider leaf, gunpowder, souchung and others. The cashier’s booth was built to resemble a pagoda. Oriental lanterns hung from the ceilings to enhance the source of teas. On Saturday nights a band played most favorite tunes including, “Oh, This is the Day They Give Babies Away (with a half pound of tea.)” Lithographs of sweet babies were handed out to the women. The new slogan became, “There’s good news for the ladies,” that being the price of tea. A splendid eight horse team of dapple gray horses pulled an elaborate wagon through the streets to advertise the store’s produce. Contests were organized such as how much did the entirety of the horses, harness, wagon, etc. weigh. The prize was to be $20,000.00. Advertising in national magazines, newspapers, circulars, and posters heralded the development of the Great American Tea Company. People were urged to form “tea clubs” and receive shipments of teas to sell to raise money or keep for themselves at a good price. Special rates were applied. The unemployed with very little outlay of money could make a wage by buying the tea and packaging it themselves ... “Sell our Sun Sun Chop or Wootang Oolong Teas. It takes very little to start with.” Showmanship vied with salesmanship at the Great American which by 1869 had grown to respectable size. What next? Coffee, that’s what ... “Our Coffee department is the largest in the country. We run three engines constantly, sometimes four and five to roast and grind the coffee. We sell none but the fully ripe, flavored coffees. Prices range from 35¢ a pound for Sultana brand (cannot be excelled) to 25¢ a pound for Eight O’Clock Breakfast Coffee (healthy and strong).” When did that third brand arrive on the shelves? Was it “ToKay?” Give me a hint. (Somewhere there’s a small yellow metal bank with the brand name on it but no time to search!!!) As roads away from the city improved, peddlers with teas, coffee and spices wandered around the countryside selling wares. Yes, spices were an addition to the company’s merchandise. In 1869 America was linked coast to coast by the railroad. A transcontinental railroad was SO good for businesses anywhere and for settlement that, of course, the Great American took advantage of the event ... “Only thirty to sixty days from China and Japan to our customers from the source.” George Hartford had been the sole proprietor of the tea company for the major part of its existence, Gilman having left after only a few years. Hartford thus was the idea man for the progress and development of the business. In 1870 it became the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company, or as it came to be more familiarly known, The A and P. By 1880 there were as many as ninety-five stores in Hartford’s “chain” as far West as Milwaukee. His ideas for selling tea, coffee and spices being accepted by the Westerners, too. That year also Hartford’s fifteen year old son, George L., joined the firm at the bottom of the ladder, learning the ropes, so to speak from the ground up!! It was he who recommended the store manufacture their own brand of baking powder, then a most exciting household product. Before BP’s reliability and success leavening was only a sometime accomplishment. Their own brand could be sold much cheaper than buying it elsewhere. It was welcomed as had the teas and coffees of two decades of the public becoming familiar with the name. By the time of the Spanish American War in the late 1890’s, peas and tomatoes were being produced with the A and P label on tin cans. John Augustine Hartford had entered into the firm’s employees, sixteen years old, and an innovator like his father. He had a strong commercial sense and respected how the company had come as far as it had. In later years as an executive he always wore a red carnation in his lapel as a tribute to his father. By 1912 the two brothers took a hard look at the organization, the operation of the business to decide it needed some modernization. As a result the most extensive transformation of any U.S. business took place. The new practices set the grocery industry on a new course although there was major suspicion for years to come. But the A&P’s ultimate success convinced the merchandisers to follow suit. Number one was the suspension of credit ... Since the “beginning of time” credit had carried the customer from pay check to pay check or longer ... When the crops came in or the cattle were sold. Cash and carry became the rule ... Carry out, deliver your own groceries ... A new thing and, perhaps, not especially welcomed by the customer. But it made the merchandise cheaper, didn’t it! Fewer clerks were needed too thus lowering the overhead. John A. Hartford’s idea was to open an “economy store” with no frills and fewer on staff. George’s senior and junior were at first suspect but agreed to try it. Within six months the economy store had run their regular store around the corner out of business. Within five years three thousand of the NEW stores had opened throughout the country ... Three new places each day for a year. Expansion continued until in 1925 the rate had increased to seven a day. It was the most spectacular change in the food industry that had ever occurred, then and now, brought about by the A&P, a first in national “chain” stores. Those methods brought convenience buying into the consciousness of the American public. The A&P’s red front was on many Main streets. Not only was the red front familiar but their interiors were familiar, too. All stores were laid out the same, merchandise being arranged alike in all stores across the nation. Mobility had entered the development of America. Housewives moving town-to-town as often as they did as years passed, could find some security in the fact that the new town’s A&P was almost like Back Home. It worked. George, Jr. and John Hartford kept in close contact with customer needs and desires. In one year alone John visited three thousand of the stores across the country. He’d “canle” eggs for freshness or slice lunch meat at the slicer, work behind the counter to talk to the customer — and clerks. George had an appointment every afternoon at two to taste the coffee blends that came in from Brazil or Columbia to see that quality was upheld. They were their father’s sons. They didn’t practice that Undercover Bogs gig. Even though the Atlantic and Pacific Company led in the transformation of food merchandising, it stayed true to its pleasing the customer methods and the personal attention of its managers, staff and executives as long as the Hartford brothers were at the helm.

Little do we realize now how that familiar red front store, rather conservative in its latter years, was such a modern marvel. We were fortunate in Lanark to have had an A&P where the aroma of freshly ground coffee greeted you as it was ground for a single customer ... Mmmmmm! There were managers such as Ben Mathias, Ralph Gifford, Jim Lindsay worked there who with Chick Engles opened the E&L Food Center across the street. The last manager recalled was Red Gaedert, a boisterous individual. Some turmoil in the late 1960’s, early seventies upset the operation nationally and many stores closed. Are any functioning today somewhere? Are Ann Page and Jane Parker still baking? Is Eight O’Clock still brewing somewhere? Blends and mixtures of coffees has outstripped Sultana and ToKay (?) but they were sure good cuppas. The picture here was among my “souvenirs.” There was no credit source.

|