Discover rewarding casino experiences.

|

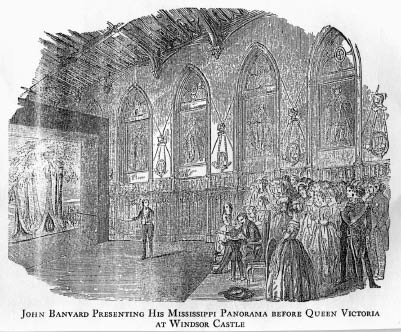

Savanna was not the star attraction in one of the first moving picture shows in 1849 but it was featured in one of the scenes of the shorelines of the Mississippi River that year. Yes, a moving picture in 1849 though not the snaky celluloid reel unwinding slowly that we know today. That moving picture was yards and yards of canvas mounted on long poles turned by hand by a system of gears before an awestruck audience to the accompaniment of music and narrative. That’s entertainment. The scenes were painted panorama, epic vistas of mid-America in the mid-century, nineteen hundred. The first such rendering, however, had been in 1788 in Edinburgh by a Scotsman depicting that city. Panoramas were not numerous because of their size and the energy it took to create one. The ones we mention here are noted because of their connection with Illinois history. They were all considered entertainment in a time when yet people mostly entertained themselves rather than participate only as spectators as we do so much today. The first of the type were called “cosmoramic views,” epic paintings of far away, exotic places that few folks had ever seen. It was a period in which people once homesteaded-in didn’t travel more than fifty miles from home. The harbor of Singapore or the Casbah, indeed, were to be seen and talked about afterward. The American of one hundred fifty, two hundred years ago wasn’t much impressed by aesthetic beauty. He was trying to survive the hardships and humdrum of everyday life but once in awhile he could be coaxed to visit the bizarre, the colorful, the curious like, perhaps, the Easterner who preferred large inspirational religious or Biblical cosmorramics, heroic figures. The Westerner (Illinoisans) desired dramatic horizons to aspire to. Illinois, the first half century of the nineteen hundreds, represented the Westerner. It was the frontier about which few knew the details. The first museum in Chicago, 1845, is said to have an excellent collection of “cosmoramic views” that the rough hewn pioneer paid money to see. Types of entertainment you paid to see were few and far between so such were sought out especially if word-of-mouth urged them and the hyperbole of advertising lured them in. The cyclorama was the next type of entertainment that became popular. It was similar to the panorama except that it was a pointing in the round. Circular buildings were specifically built in which to mount them. They had seating in the center on the floor where people could sit to oooh and aaah! Epic scenes, too, were the subject. The Great Fire in Chicago, 1871, was the subject of the theater there ... Soaring flames, roofs falling in, people fleeing on a canvas fifty feet high and four hundred feet in circumference. The audience could feel so immersed in the scene that they might become emotional over the breathtaking devastation. Its artist, Cephus Collins, won several commissions world-wide after its exhibition, painting historical, heroic and inspirational events, battles and such, because of that Chicago cyclorama. On his retirement he came to live in Illinois at Bement and Decator following a stint at Iowa State College as a penmanship instructor. The cyclorama was painted from some high point such as a steeple, cupola, capitol dome, a tall building — anywhere four directions could be seen to be painted “in-the-round.” It appealed to the creative artist as well as the audience. Inventor, Robert Fulton, paused in his thinking about perfecting the steamboat to go to France to paint a cyclorama of the City of Paris. It was he for whom our neighbor, Fulton, in Whiteside County was named. While the panorama had been a type of entertainment for years, the moving picture panorama took some time to come to mind but, naturally, of course, in the modern age, the Age of the Industrial Revolution, no less, movement, motion evolved in everything from steamboats to panoramas. They had such themes as “Conflagration of Moscow,” “The Funeral of Napoleon,” “City of London” were only a few to be seen in Chicago. The idea of a moving picture panorama had come about as early as 1839. After all, there were creative Americans in every age! ... That 1834 creator was John Rowson Smith with the assistance of John Risley. Between the two they’d created the first, as far as is known, of the Mississippi River valley and tributaries and had shown it in Boston. Such entertainments had accompanying attractions such as music with narrative, too. In the case of Smith and Risley, it could have been that Risley performed as the picture unwound for he was an acrobat. He may well have showed his skill at the moving picture show. Mention of Risley is intentional, although only brief mention is made in reference. PDQ Me is searching for any information of the Risley family who lived in Lanark, c. 1900. They were apparently a fun-loving and out-going family according to the newsy tidbits found in old newspaper files. One son became a pro/semi-pro baseball player of whom we’d like to learn more. An acrobat, John Risley, could well have been an ancestor swinging in the family tree! After several years touring in the United States they took the moving picture to London where in 1849 the narrative was published then in Berlin in German in 1851 and in Christiana in 1852. It is interesting to note that important study was made of how those panoramas were in affecting immigration from Norway to America. They were travelogues influential in promoting such historical change. America pictured in such a positive, beautiful manner was the best advertisement possible. The hyperbole of overdone ads and pamphlets, came in a close second. The promise was too much to resist. St. Louis, Missouri was the, apparently, the center for panoramists. Several of those who created them seemed to have originated there. Rowson Smith, for instance, was a theatrical scene painter there as early as 1832. Even though it was a bustling, thriving river port, it is almost certain that Smith would have known John Banvard who was recognized as one of the great panoramists. He had a museum in St. Louis so was in close touch with the public. In 1840 he began sketching Mississippi scenes in preparation for a panorama, a topic that gripped the art world and ordinary citizen because of its potential. He descended the river in a small skiff, drawing and noting the landscapes. He obviously painted at a leisurely pace because he was still working on it in 1846. The canvas was touted as being “three miles in length.” It was exhibited first in Louisville where he’d had a special long building constructed to house the work in progress. Then it was taken to New York and Boston where in sixteen months, four hundred thousand people came to view it. Taking it on tour in England it became a sensation at Egyptian Hall, Picadilly, where there were six hundred thousand paid admissions to see the “Father of Waters.” In the spring of 1849 a private showing was given to Queen Victoria and her household staff at Windsor Castle. John Banvard’s original moving picture had scenes from the Falls of St. Anthony in Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico. There were separate panoramas of the Missouri River from the mouth of the Yellowstone plus the Ohio River valley, too. As time marched on and the Civil War opened, Banvard added a “War Section” in 1862 illustrating battles and events of that terrible chapter in our history. Naval and military highlights were illustrated. Banvard had long desired to paint the world’s largest picture and probably succeeded. He attracted large audiences and enjoyed financial success with it. That, of course, inspired others to use the same idea as a money-maker. The much-noted painter of the native American at the early day, Seth Eastman, gave it a try, sketching river scenes as he left his station at Ft. Snelling in Minnesota to an outpost in Texas. Other artists, however, are noted here, one of them being Henry Lewis who for many years was given credit for being the panoramist of moving picture notoriety. Research, however, has proven that to be incorrect although he was energetic in creating the wondrous scenes of the Mississippi River valley of which we are a part.

Perhaps, the attention he’s received is due to the fact that he left behind many diaries, notes, journals from which valuable history could be taken. His correspondence has been valuable in learning of life by the rivers mid-nineteenth century Illinois, having Ol’ Man River as its entire western boundary has been a boon historically, economically, socially. We should think of its importance as pointed out by the moving picture of yesteryear. Next week continues with mention of Savanna’s part in the “movies” of the past. John Rowson Smith who was thought to have been the earliest panoramist included the following in his narrative text: “Illinois farms (were) formed by the hand of nature can be purchased for 1.25 an acre and the region is a greater El Dorado than the gold mines of California.” But we know that, don’t we!!!

|