Discover rewarding casino experiences.

Please Don't Quote Me Quoth the Raven, “Nevermore.” Edgar Allen Poe wrote that famous line, quoted for evermore. |

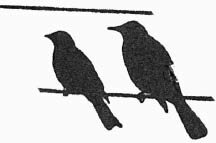

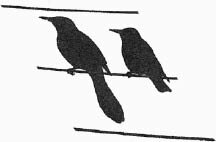

Ravens have appeared in legend and literature. Solomon’s women had “raven’s tresses.” Myth had it that Ravens once were all white but because of some sinful act were turned black as punishment. Being scavengers, Ravens feeding on dead carcasses (or corpses) were associated with the “darkness of death.” A bad reputation, you say! Oh, but the Raven is quite sociable. Their brains are large in proportion with their bodies and they use it. They can count. They can imitate the human voice or sounds. They also mate for life like some humans. The Raven is a large bird in comparison to the other backyard birds we see in our territory and to the other black birds. They can exceed a little over two feet in length while the Crow, for instance, may grow to only twenty inches. If the birdwatcher can see the throat of the Raven it can identify it by the ruffled feathers at its throat. The silhouettes here show the differences. They are from Peterson’s “Field Guide to the Birds, 1956.” Raven’s flight is hawk-like in that it soars and flaps, soar and flap on horizontal wing. A crow’s wings bend slightly upward instead of flat out. Raven’s call is coarse ... “cr-r-r-uck” or “prak” while that of the crow is the oft-imitated, “caw caw!” The noises are sometimes accompanied by head bobbing as they strut about the yard or roadway. Indistinguishable noises might also be heard but so far they aren’t identifiable. This is usually in the spring when courtship, nest building occur. The nest building of the Crow may be an interesting time for the dedicated birdwatcher. They busily carry twig after twig and begin several nests or partially. They don’t just pick the sticks up off the ground but harvest them by walking out on limbs and breaking off the necessary building material.

‘Way back in medieval times when lords ruled the manors and had servants, serfs to show authority over, the lowly peasants would search for trees with Crows nests and pick up sticks that had fallen to the ground to build their meager fires! Crows are selective, too, in their migratory habits. Crows here in the Midwest actually do migrate from the Canadian provinces into all the Midwestern states. Those birds over east only migrate a few hundred miles. In the South those birds stay all year ‘round. Crows are of the Corvidae family that also includes rooks, jays, jackdaws and choughs, the latter being a black bird from Cornwall, England where the crow was associated with the spirit of King Arthur. Scotland has its “corbies,” a word that comes from the French corbeau meaning crow. Actually Crow comes from the Anglo-Saxon crawe, an imitation of their call. Through etymological evolution we now have roosters crow and Crows caw (without the “r”). The rook, a Eurasian bird, gets its name from Old Norse, a word describing its hoarse croccky voice.

Corvidae are found all over the world as you can tell from these short anecdotes. There are many more instances using both names especially crow ... Crow’s feet, crow’s nest, crow bar, scarecrow, etc. Ravens’ scientific name is Corus corax from the Greek for “croaker,” harsh and guttural. But its common name, Raven, got its label from Old Norse, hrafn, “to clear one’s throat!” Over ages of time the Scandinavians dropped the ‘H’ so the word lost some of its distinction and became simply “raven.” While mentioning Norsemen, their ancient god, Odin, had two Raven associates; Hugin, (his thought) and Munin (his memory). Ravens are closely associated with the supernatural, perhaps because they can talk. A person with ESP had “Raven’s Knowledge.” Author Charles Dickens had a pet Crow named “Grip” which he put in his book Barnaby Ridge. It would often call out, “I’m a Devil.” Some may have believed that because Corvidae are carrion eaters, feeding on roadkill and at long periods in history when bodies were strewn about from wars, starvation, disease and so forth they fed on people. Even though Corvidae are more bold and daring than more skittish birds, their bills are not strong enough to penetrate skin so they pluck at the eyes, human or animal, and go from there! Such ghoulish activity seemed to we humans, certainly built up lore over the centuries. The birds are omnivorous but prefer meat. They are considered around the globe to be the most highly developed and adaptable of birds so in your conversation with the Corvidae you might have some back-talk. Just don’t close your eyes. You can blame Eugene Schefflin for the score upon scores of those black birds you recognize as Starlings. That bird, Sturnus vulgaris, originated in Asia. It was not a native bird of North America but came here in 1890 brought by the “American Acclimatization Society” which supported Schefflin in wanting to bring all the birds and flowers mentioned by Shakespeare in his works ... A cultural project? The Starling was one of the birds having been mentioned in “Henry IV.” Forty pair were set free in Central Park, New York and from them we have another black bird. Some put it about that the birds were to feed on insect pests but they became pests on their own. They number in the millions and like the Grackles, and other black birds, love to roost anywhere—from a few hundred to a quarter million. Starlings have a roosting habit that speaks but of them. A few hours before roosting time they will start towards that site but dither along the way, join other groups then dive headlong into the roosting area as if showing off? Reference books tell us all about the habits of Starling such as the Crowing, the Wing Wave (it has to do with sex), Sidling, Wing Flicking, Bill Wipe and much, much more. Space and my lack of patience and interest stay more news of the Corvidae, etc. The Starling may be among the least liked of our birds. They swoop and dive, perch on branches or utility wires, eat insects, etc. What more do we want? Just as the Starling may be considered a nuisance for the birdwatcher, its close look-alike, the Mynah, was introduced to Hawaii to rid the sugar cane fields of cutworms but proliferated so much they almost choked out the native birds of the Islands. The Hindu, however, wanted them to nest in their Temples for good luck as did the Druids at Stonehenge. They need only a hole 1½ inches in diameter to begin building. Despite their reputation and character, the Starling does have some positive aspects besides its sheen black feathers. Mozart, the composer, while shopping one day, heard the Starling in a shop whistling a segment of his G-major Concerto and had to have the bird ... Some bird. He had it three years before it died, then buried it in the garden with a marker with a sad epitaph written by the musician.

Staer is the Anglo-Saxon word for the Starling and derives the “ing” from a suffix from diminutive. It identifies the bird, too, in winter when its feathers become speckled lightly so that when they fly overhead it’s as if the stars were twinkling. Well, you can work at imagining that! Star speckled bird. Star-speckled sky, okay. One story told about the fabulous numbers of them, at times so great that in 1949 hundreds lit on the hands of Big Ben, the iconic landmark clock in London so that they halted the hands movement ... Stopped time, if you will. Parliament ordered immediate extermination of Starlings. That was unlike the Raven in Britain so revered that there is a keeper today for them at the Tower of London. It following a decree by King Charles Ⅱ to whom a soothsayer told that the nation would fall on hard times if Ravens left the Tower so they were allowed to live there ever since. Only the dear British make it a real ceremony. Watch for those black birds around us. They’re worth the curiosity.

|