Discover rewarding casino experiences.

|

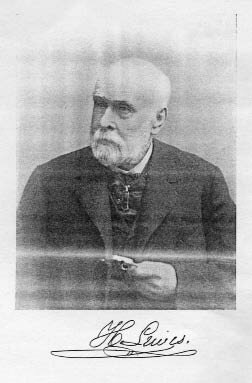

While John Banvard had painted at a leisurely pace (last weeks), Lewis painted furiously. No money accumulated while the paint dried! Within a year the canvas was completed but its premier in its “home” city studio was not successful. Lewis despaired. However, back in St. Louis people came out to see the latest of the panorama. Lewis began planning a tour of the East coast. At Washington, D.C. he collected testimonials from leading politicians, even President Zachary Taylor. By the time they’d reached Bangor, Maine however, he was wishing for someone to buy it. He wrote his brother George in St. Louis that he had no alternative but to take the moving picture abroad. That winter he traveled around England but barely made expenses. On to Holland they enjoyed a successful tour and in fact were responsible for many Dutchmen to emigrate to America because of the wonderful scenes luring them to come. Despite his strenuous efforts, Lewis failed to sell the panorama even with its positive message. Not until 1857 did he succeed. It was bought by Hermen Hermens, probably a German, don’t you suppose, but who had a plantation in Java to which he sailed only paying half the set price of $4,000. It is believed that the balance was never paid. It was put aboard ship toward the South Seas never to be heard of again. Most of the seven Mississippi River valley panoramas were destroyed by fire which isn’t an odd coincidence because lighting of theaters was by candlepower or lamp light, a major danger. A few paintings here and there are thought to have been part of panoramas originally. Some were merely destroyed when they became obsolete as entertainment. Yet in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, “the Battle of Gettysburg” panorama was featured at the Lanark Opera House, so some survived for awhile. Only one entire moving panorama of the Mississippi River theme is known to be in existence and that is at the City Art Museum in St. Louis. In 1950 it was exhibited at its centennial. Its artist was John Egan who painted it in 1850 from sketches done by Montroville Dickeson of Philadelphia. Dickeson’s idea was to portray the archeological, botanical and geological of the Mississippi and Ohio river valleys. Of the latter, for instance, there were sketches, then paintings of Cave-in-Rock on the Illinois bank of the Ohio that had long been shelter for the native American and a hideout for river pirates in the “modern” day. To give dramatic effect, painter John Egan used mica and tinsel to create mysterious lights in the “alleged” interior of the cave. There were supposed petro glyphs on the walls, as well as ancient skeletons and mummified bodies to awe the viewer or create fear from the eerie moving pictures. Dickeson had been an avid collector of Indian artifacts, stating that he’d opened over a thousand of their burial mounds and had 40,000 relics from them in his collection, some of which were on display as part of the movin’ picture show. Panoramists vied passionately with one another to draw in the patron by using such come-ons as the artifacts, life-like miniature props like the flatboats or steamboats before mentioned, even acrobats as well as the musical accompaniment with the written narrative to explain the scene of the moving picture. As for painter Henry Lewis’ panorama, it had proved to be a failure for some reason. It became a canvas albatross he wanted to be rid of financially and emotionally. By 1853 he had moved to Dusseldorf, Germany where he lived until his death in 1904. At one time he served as agent for the American consulate in that city which during that period was a center for artists especially landscapists. He returned to the United States only once and that was in the 1880s when he came to St. Louis for a family wedding. It is thought that while still in the U.S. in the early 1850s he was in contact with a German publishing company to discuss the printing of a book of the narrative of the text with the panorama that would have lithographs of scenes from the sketches he’d made in preparation of the moving picture. Meanwhile, Lewis had married Marie Jones who was the English governess of the household of Hermen Hermens who had bought the panorama. They had a happy marriage, she believing they should take on a large house with many rooms so that they could take in roomers to financially support themselves, she to manage and the artist to paint or teach and study. The book idea went slowly forward. Das Illustritre Mississippithal was the title of the book that was to be printed in both English and German in twenty parts each with four-colored lithographs a piece. In 1854 three parts were published in both languages; 1855 another three parts but only in German. A gap ensued so that not until 1857 were the balance, fourteen, printed and only the German version. An unknown number were assembled and bound, those in German. The English edition seemed at a standstill. Lewis had complained that the books were “got up” in a very common way, not in the mode the contract had called for. The publishing house, Arnz and Co. had gone out of business. (Henry Lewis seemed never to be at the right place at the right time). The owners of the printing house had fled the country, supposedly to Australia and had defrauded many persons of large sums of money. The book fell into the hands of a book dealer in Bonn, a university town. The lithographs were given out to students or customers and the printed pages sold for waste paper. Looking back it is know known that had the German editions been marketed properly and the English version printed and promoted both would have sold well due to the superior quality of both text and engravings. Reviewers and readers of it have praised it as the best of its kind but unfortunately Henry Lewis did not receive the accolades he deserved. Nor the financial success he needed. Not until well into the twentieth century were his diaries discovered, the notes in them praised for their detail and character and the lithographs for their excellent quality. It was well-told chapter in our history. Being a part of it we taken in being part of the panorama here Northwest of Illinois whose western boundary is the Mississippi. Dusseldorf, as an art center drew many artists who would become famous here in the United States among them George Caleb Bingham and Albert Bierstadt who were painters of the Great West and native Americans. Lewis at one period sent paintings to Bingham in St. Louis and to other art dealers as well to exhibit and market but apparently there was no fashion in landscapes of Americana, at least those scenes chosen by the one-time panoramist. His “romance” with the Mississippi Valley and its varying scenes never waned. Probably no more than twenty copies exist of the 1854-55 edition of Das Illustritre Mississippithal those in American libraries. German editions when destroyed when Dusseldorf was bombed in World War II. A second German edition was printed in 1923 but it is also rare. The Minnesota Historical Society at St. Paul in 1967 purchased one of two fragments of the English version to have it reprinted, the only complete edition of the “Valley of the Mississippi, Illustrated.”

To quote the “American History Illustrated,” 1982 that states, “His paintings of the river are the most extraordinary collection ever created. He never lost his romance with the river although it was an ill-paying proposition in every way. It is unequaled in American art.” And what, you ask, brought about the end of the moving picture painted panorama? Technology. Photography. Mid-century eighteen hundreds the camera’s eye, not the artist’s hand copied the scene instantly ... The Gold Rush, Isthmus of Panama, disconnected views of a trip from Chicago to Shawneetown or St. Louis, the prairie, the bayou, battle scene of the Civil War all captured by the camera in a black and white photographed panorama that continues into the future.

|